(Pic: ‘Schooner on calm waters’ by Charles Heaphy, 1850s (?), Alexander Turnbull Library collection)

Shipping in Wellington, 1850-1870

In the 19th century travel between towns in New Zealand was dictated by the rugged and often impassable terrain of the intervening bush, with fast-flowing rivers and treacherous hills often preventing the construction of safe roads. Railways did not spring up until the 1870s, and even then it took decades for the most troublesome terrain to be breached. The North Island main trunk line between Auckland and Wellington was not completed until 1908, so for a generation of travellers a journey between the two cities generally involved a sea journey in boisterous waters, either the whole way or via New Plymouth, which was linked to Wellington by rail from 1886 onwards.

Aside from the ever-present demand for passenger transport, the burgeoning colonial economy required a busy transport infrastructure to move farm produce and timber to markets, and distribute the consumer wares imported from England and other nations. The terrible state of the roads meant that much of the longer-range intra-colonial transportation in New Zealand was undertaken by coastal shipping. Larger vessels linked the main ports, initially sailing ships but later steamers as well; these fed consumer goods to merchants and brought commodities for shipping to the eager markets of England or Australia. Smaller boats also played a vital role, acting as the Victorian equivalent of modern delivery trucks, dispatching individual cargoes to tiny ports in the colonial hinterland that could not attract the larger vessels.

Wellington was founded in 1840, and was the first New Zealand Company settlement. Its central location on Cook Strait assisted the town’s commercial growth, as its superb harbour, Port Nicholson, became an ideal point of trans-shipment for the entire colony. From the very beginning of the colony, shipping links were of the utmost importance to the Wellington economy, and particularly to its shopkeepers:

[In Wellington in the 1840s] the shops sold a practical range of merchandise, as was evident by the number of bakers, butchers, clothiers, furnishers, tobacconists, ironmongers, saddlers and chemists. All their stock arrived by sea, either from other New Zealand ports or Australia and England, and was distributed from bond stores and warehouses. New bulk shipments were advertised widely in the newspapers and caused much excitement among shoppers.

- Terence Hodgson, Colonial Capital: Wellington 1865-1910, Auckland, 1990

The shipping advertisements mentioned above often form the largest part of the slim colonial newspapers of the time. Online resources such as Papers Past now enable us to examine newspaper archives of the time with ease, so as a small project I decided to examine shipping reports in Wellington over three decades, to see if there were any noticeable changes. To do this, I examined three Wellington newspapers, each printed on or around Waitangi Day – one each from 1850, 1860 and 1870. (By 1880 Wellington had a rail link to Masterton, and by 1891 the capital’s rail links extended to New Plymouth and Napier, so by that time coastal shipping occupied a less pivotal role in the colonial transport infrastructure). By the time of the 1870 publication, Wellington had become the national capital, the seat of government having moved from Auckland in 1865.

6 February 1850: The New Zealand Spectator and Cook’s Strait Guardian

For those seeking passage out of Wellington, the front page of the Spectator advertises the availability of accommodation on the regular trading clipper barque Cornelia (372 tons), which was shortly bound for London direct, while for those wishing to travel southwards, the ‘fine fast sailing schooner’ Dolphin was advertising for passengers to Otago. (Dunedin had been founded two years earlier in 1848; the first of the settler ships to populate the new colony at Christchurch did not arrive until December 1850, ten months after this newspaper was published).

Page 2 also contains passage advertisements for the ‘fine fast sailing barque’ Woodstock (300 tons), bound for London direct on 1 March, and ‘to sail positively on the 10th February, the fine fast sailing first-class Barque’ Thames (407 tons), bound for California. The latter would doubtless be carrying passengers stricken by gold fever, given news of the great Californian gold rush of 1849 had already reached New Zealand, although one commentator of the time believed otherwise. In an essay lambasting Auckland, a New Zealand Company agent wrote in 1851 that:

As an instance of colonisation, it was altogether rotten, delusive and Algerine. The population had no root in the soil, as was proved by some hundreds of them packing up their wooden houses and rushing away to California, as soon as the news of that land of gold arrived. In Cook’s Straits not half a dozen persons were moved by that bait.

- William Fox, The Six Colonies of New Zealand, London, 1851

(Fox later entered politics and achieved four terms as Premier).

Other front page advertisements record the contents of ship manifests from the Cornelia and others including the Minerva, William and Alfred, Inconstant, Kelso, Pekin and Thames. The ship cargoes, some of which had arrived up to several months previously, reflected the demands of a burgeoning young colony, with building supplies and grog featuring prominently. As an example, here’s the advertisement of Hervey Johnston & Co. (which was originally published on 21 November 1849):

For sale ex “William [and] Alfred”

- First quality Sydney flour in 100lb bags

- Hunt’s treble diamond Port Wine in quarter cases

- Manila cigars, Nos. 2 and 3 (new numbers)

- Manila coffee

- Qr. cases of Glenlivat Whiskey, 11 o.p.

- Rice and Scotch Pearl Barley

- An assortment of Drapery suitable to the present wants of the market, consisting of:

- Bleached Linen Drills assorted

- Rough Hollands, Osnaburghs

- Brown Cheese Cloths

- Irish Linens, &c., &c.

The newspaper’s shipping intelligence column shows a busy harbour, with 16 commercial vessels in port ranging from the hefty Inconstant (589 tons), which later became Plimmer’s Ark, and General Palmer (573 tons), down to a selection of much smaller schooners and cutters ranging from 15 to 82 tons. These were joined by three naval vessels visiting the port: HMS Fly (18 guns), the training ship HMS Havannah (19 guns), which (if I have identified it correctly) was so elderly that it had an illustrious history in Napoleonic War actions, and HMS Acheron (a 6-gun paddle steamer).

The important role played by the smaller vessels is seen in the details of the cargo of the schooner Old Man (15 tons) under Captain Smith, which arrived in Wellington from the Manuwatu on 4 February, carrying a cargo of ‘3 1/2 tons wool lashing, 1 ton flax, 128 planks’.

Departures listed over the past week included six small vessels dispatched to various parts of the colony: Taranaki, Port Victoria (soon to be renamed Lyttelton), Manuwatu, Castle Point, ‘Castle Point and Otago’, and Waikanae. The latter run, by the 8-ton schooner Emma Jane (8 tons, Captain Brown), indicates how even settlements in close proximity to Wellington were easiest reached by sea. The Emma Jane’s cargo shows the many requirements of the colonial way of life: ‘1 chest tea, 2 bags sugar, 1 case gin, 1 hhd. [hogshead?] brandy, 1 bag sugar, 1 bag salt, 1 box soap, 1 package canvass, 3 casks bottled porter, 1 bag flour, 1 bag bread, 4 flagstones, 10 bags flour, 1 cask beer, 3 bags potatoes’.

7 February 1860: The Wellington Independent

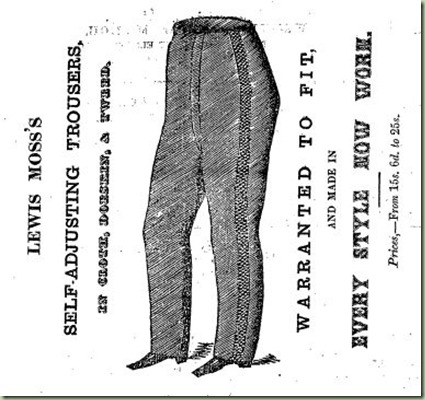

Ten years later the Wellington Independent portrays a stronger, wealthier colony. While the 1850 newspaper was four sheets long and bore almost no embellishments such as illustrative engravings, the Independent in 1860 is six pages long and boasts several sizeable engravings, including a huge graphic on page six advertising Lewis Moss’ clothes for men: pictured are fine items such as the Double-Breasted Oxonian jacket and Lewis Moss’ Self-Adjusting Trousers.

Readers requiring passage out of New Zealand were served by a multitude of prominent advertisements, and those seeking passage to London would have noted messages offering places on clippers such as the Melbourne, Eclipse, Wild Duck, Zealandia, and the Robert Small. A new sense of punctuality is evident in the advertisement for the Arthur Willis, Gann & Co. line of packet-boats to London, with a list of 11 large sailing vessels ranging in size from 800 to 1600 tons making the long journey on regular schedules. Closer to home, the clipper brigantine Ariel was loading freight and passengers for Melbourne via Nelson and New Plymouth, and a sign of modernity was evident in the listings for two steam vessels making domestic journeys: the SS Oberon was intending to run fortnightly between Wellington and Otago, while the SS White Swan was seeking passengers and freight for Napier and Auckland ‘on or about the 1st and 14th of every month’. (The White Swan entered the headlines two years later when it sank whilst carrying government officials and records to Wellington).

Also of note is the connection between the popular sport of horse racing and the shipping trade. The size of the advert on page 2 for the 1860 Hutt River Races, to be held on 14 and 15 March, indicates considerable public interest in the event. This interest is echoed in the page 1 advert for a special sailing of the well-known steamer, SS Wonga Wonga:

Canterbury Races

February 14th, 15th, and 16th, 1860.

The SS “Wonga Wonga”, Capt. RENNER, will be despatched for Lyttelton, (should there be a sufficient number of passengers engaged previous to the 1st February), on SATURDAY, 11th February, at noon, and return direct to Wellington on the 17th February, the day after the Races are concluded. DUNCAN & VENNELL, Agents, 24th January, 1860.

While this might not seem particularly noteworthy, it is worth observing that a mere 20 years after the founding of the colony a substantial commercial venture – a speculative ship charter of a sizeable vessel – was undertaken with the understanding that there was sufficient consumer demand for summer holiday transportation hundreds of kilometres south for a sporting fixture. It is unlikely that the journey was in doubt at the time of publication, given the 1 February deadline had already passed, so presumably the promoters were seeking a few more passengers to fill out the manifest.

The scale of intra-colony passenger transport can be seen in the shipping intelligence column, which amongst a broad selection of ship movements records the visit of the Airedale:

The I.C.R.M. Company’s steamer Airedale, Captain Johns, arrived in this harbour on Wednesday last, from Manukau, Taranaki and Nelson. She brought 20 cabin, and 93 steerage passengers besides a fair cargo of merchandise. The steerage passengers are parties who proceeded to Auckland under the land regulations of that province, and are now on the way to Otago. The Airedale sailed the same day as she arrived, for Canterbury and Otago, with 28 cabin and 97 steerage passengers.

The complicated itinerary of the Airedale shows the nature of the trade, with vessels making numerous stops at ports the length of the country rather than relying solely on single point-to-point journeys. Under this arrangement, a passenger wishing to travel on the Airedale from New Plymouth to Wellington would have to make an intermediate stop at Nelson before arriving at Port Nicholson.

It’s also worth noting that the column lists the names of the Airedale’s cabin passengers, but only a few of the steerage passengers’ names.

Stock manifests, which appeared in a prominent location in the 1850 newspaper, now appeared further in on page four and six of the 1860 equivalent. This indicates that while the contents of ship cargoes was still newsworthy enough to form part of advertising campaigns. If the adverts are a reliable guide to consumer tastes, then Wellingtonians were most eagerly awaiting the arrival of alcohol and clothes, with plentiful quantities of booze and a wide variety of fabrics for sale. While many of the adverts are too long to quote in full, one briefer note placed by W & G Turnbull & Co. is fairly representative:

Ex “Countess of Fife”

- 200 doz. Ginger Wine

- 240 doz. Bottled Stout, Quarts

- 160 doz. Bottled Stout, Pints

- 16 cases assorted drapery

- 2 cases Candied Peel

Overall, the 1860 newspaper indicates a stronger economy befitting a mature colonial town, with considerably more plentiful shipping services and a wider range of merchandise delivered by those services.

7 February 1870: The Evening Post

By 1870 Wellington was 30 years old, and was firmly established as the nation’s capital. The four-page Evening Post contains three noteworthy items distinguishing it from the 1860 newspaper.

First, on page 1, an advert for Cobb & Co.’s Telegraph Line of Royal Mail Coaches from Wellington to Patea, apparently a new service, indicates that land transportation was becoming more feasible. The Post indicates that the journey was scheduled to take two days from end to end, with an overnight stopover in Wanganui. (The Post’s back page also details the company’s services to the Wairarapa, departing every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday morning).

Second, the report of the coach’s progress and of other details in the Post’s shipping intelligence column is labelled as being received ‘by electric telegraph’. By 1870 improved land transportation had also been joined by instantaneous communication to various parts of the colony, enabling details of the overseas newspapers to be transmitted to most parts of the country when they reached a New Zealand port. (Here’s a map of the telegraph network in 1868; the country was not linked to Australia, and therefore the rest of the Empire, by an international undersea telegraph cable until 1876).

Third, the front page advert placed by the Provincial Government of Otago seeking tenders for the construction of the Otago Southern Trunk Railway from Dunedin to Balclutha indicates that the railway construction boom that was to grip New Zealand in the 1870s and provide strong competition for coastal shipping was just around the corner.

The Post’s shipping adverts are clustered on page 3. Passengers wishing to depart New Zealand are served by only one advert, and that for a departure from Auckland - that of the Circular Saw Liner Alice Cameron, bound for New York via the whaling port of New Bedford, Massachusetts. The clipper Melita was also advertising its upcoming trip from Wellington to London, but this appears to be solely for a cargo of wool rather than paying passengers.

The newspaper lists plenty of New Zealand and trans-Tasman shipping routes though, and these are well developed when compared with earlier decades. The Circular Saw Line lists three ships on provincial routes including the venerable Airedale, still making the same multi-stop journey as in 1860. McMeckan, Blackwood & Co.s’ steamers show the range of ports offered by one shipping line in a calendar month:

Messrs. McMeckan, Blackwood & Co.’s steamers are appointed to leave Wellington on or about the following dates during the month of February:

10th – RANGITOTO, for Nelson, Greymouth, Hokitika and Melbourne

15th – TARARUA, for Lyttelton, Otago, Bluff and Melbourne

22nd – CLAUD HAMILTON, for Lyttelton, Otago, Bluff and Melbourne

OMEO, for Nelson, Greymouth, Hokitika and Melbourne.

For freight or passage, apply to N.Z.S.N. Co. Limited, Agents.

It is interesting to note that in 1870 it was possible to travel directly to Melbourne from Hokitika and Bluff!

The shipping intelligence column, as mentioned above, contains not only port movements from Wellington, but also telegraphic reports from Port Chalmers, Lyttelton, Napier and Hokitika, so interested parties could determine if a ship containing loved ones or valuable cargoes had reached its destination unscathed. (For a more detailed understanding of the effect that the telegraph had on the 19th century society and economy, read Tom Standage’s excellent book, ‘The Victorian Internet’).

The Wellington shipping report contains the standard mentions of small and medium-sized vessels travelling to and from regional ports, with the smallest ship being Captain Thompson’s ketch Mosquito (14 tons) from the Manuwatu, which had arrived at Wellington on the day of publication. Expected arrivals included the SS Rangitoto ‘from Melbourne, via the South’ on the 9th, and the William Cargill from London.

As in 1860 the summer season encouraged a holidaymaking venture. The Airedale had departed on the morning of publication with no less than 500 excursionists on board for a journey to Picton in the beautiful Marlborough Sounds. In its large editorial columns, the Post commented:

The excursion trip of the Airedale to Queen Charlotte’s Sound seems to have taken remarkably well, and to have exceeded the expectations of those who projected it. As many as could possibly find room got on board this morning at the wharf – people who professed to be adepts at reckoning live stock said there were 500 – and about a hundred more were, with the utmost difficulty, kept back. Whether or not they all paid the 5s will remain something of a mystery. The weather being so beautifully fine, there is little doubt that the trip will be a very pleasant one. Five hundred excursionists landing at once in Picton, will be quite an event for that forlorn town. Had the N.Z. Co. have prepared another steamer to start an hour after the Airedale, it is most likely that she would have picked up a full freight. These excursions afford a very pleasant and healthy means of enjoying a day’s relaxation, and it is to be hoped the idea will not be allowed to drop.

The regularity of shipping services and the scale of one-off events like the Airedale day charter show that the shipping lanes were still of considerable importance to Wellington and New Zealand in general. Later years would see a diversification into other modes of transport, but the changes in shipping networks from 1850 to 1870 mirror the growth of the colony from a fledgling settlement into a capital city and centre of trade.

No comments:

Post a Comment