Shackleton and his crew set off from Plymouth in August 1914 at the outbreak of the Great War, having petitioned the Admiralty to offer their services to the war effort, only to receive a one-word telegram ordering them to ‘proceed’. Apart from brief calls at Buenos Aires and South Georgia, the expedition was then completely out of contact with the outside world as the war progressed.

The long and arduous entrapment of the expedition crew in the Antarctic ice are stuff of legend. After the sinking of the Endurance in November 1915, the famous 1300km voyage of the tiny boat James Caird from Elephant Island to South Georgia to summon aid is rightfully described as one of the greatest feats of maritime navigation in modern times.

Upon finally reaching the Norwegian whaling station at Stromness in May 1916, the exhausted and relieved party begged for news of the outside world, having been totally isolated from developments. Shackleton recites the scene in South!:

Shivering with cold, yet with hearts light and happy, we set off

towards the whaling-station, now not more than a mile and a half

distant. The difficulties of the journey lay behind us. We tried to

straighten ourselves up a bit, for the thought that there might be

women at the station made us painfully conscious of our uncivilized appearance. Our beards were long and our hair was matted. We were unwashed and the garments that we had worn for nearly a year without a change were tattered and stained. Three more unpleasant-looking ruffians could hardly have been imagined. [Shackleton’s navigator, New Zealander Frank] Worsley produced several safety-pins from some corner of his garments and effected some temporary repairs that really emphasized his general disrepair. Down we hurried, and when quite close to the station we met two small boys ten or twelve years of age. I asked these lads where the manager's house was situated. They did not answer. They gave us one look—a comprehensive look that did not need to be repeated. Then they ran from us as fast as their legs would carry them. We reached the outskirts of the station and passed through the "digesting-house," which was dark inside. Emerging at the other end, we met an old man, who started as if he had seen the Devil himself and gave us no time to ask any question. He hurried away. This greeting was not friendly. Then we came to the wharf, where the man in charge stuck to his station. I asked him if Mr. Sorlle (the manager) was in the house."Yes," he said as he stared at us.

"We would like to see him," said I.

"Who are you?" he asked.

"We have lost our ship and come over the island," I replied.

"You have come over the island?" he said in a tone of entire disbelief.

The man went towards the manager's house and we followed him. I learned afterwards that he said to Mr. Sorlle: "There are three funny-looking men outside, who say they have come over the island and they know you. I have left them outside." A very necessary precaution from his point of view.

Mr. Sorlle came out to the door and said, "Well?"

"Don't you know me?" I said.

"I know your voice," he replied doubtfully. "You're the mate of the Daisy."

"My name is Shackleton," I said.

Immediately he put out his hand and said, "Come in. Come in."

"Tell me, when was the war over?" I asked.

"The war is not over," he answered. "Millions are being killed.

Europe is mad. The world is mad."

---

[Above: Frank Worsley statue, Akaroa waterfront, 19 June 2009]

Shackleton’s associate, Frank Worsley (DSO and Bar, OBE, RNR), is the subject of an excellent exhibit at the Akaroa Museum on Banks Peninsula, which honours the town’s local hero. Worsley (1872-1943) played a major role by captaining the Endurance and navigating the James Caird during its perilous open-sea voyage to South Georgia, and in 1931 wrote a highly successful account of the adventure, entitled Endurance. The New Zealand Railways Magazine published a biographical piece on Worsley in October 1933 as part of its series on famous New Zealanders, and observed that:

If ever there was a man who could be described as a “Sailor of the Sail” it is Frank Worsley. And now, after a lifetime of hard-weather seagoing, when most men of his age are expectant of easy retirement, certainly when a man of his national services and achievements should be enjoying a comfortable pension, he is still ready for a job of adventure. For Worsley is one of those whose hearts are eternally young.

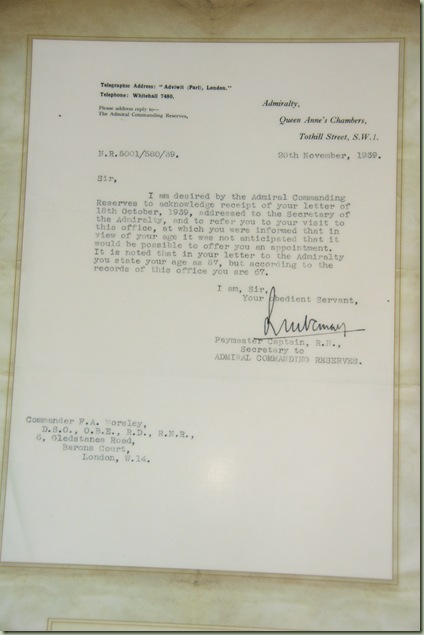

Worsley was a true adventurer. He played an active role in Great War naval service, commanding a vessel that sank a German submarine, tried his hand at treasure-hunting in Central America in the 1930s and even tried to falsify his age to enlist in the Navy again as war returned in 1939. Below is the reply he received from the Admiralty, pointing out that he was in fact aged 67, not 57:

Still, you can’t blame him for trying!

No comments:

Post a Comment