|

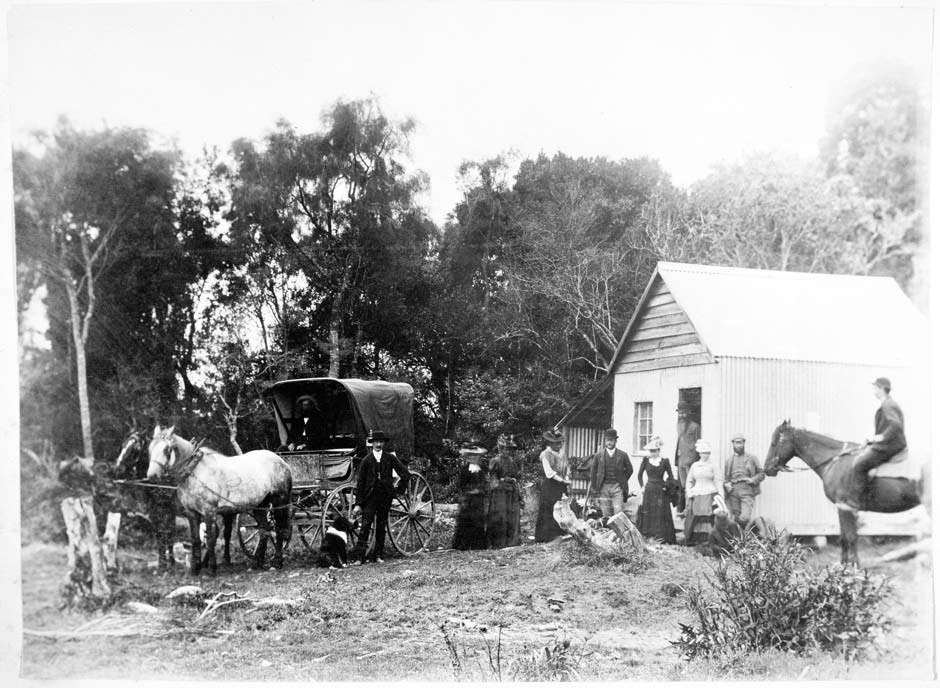

| Women voting in 1893 (via NZHistory) |

The women of New Zealand are the first who under the British flag have been enfranchised by virtue of their womanhood. It has been said, no doubt with a considerable degree of truth, that a large proportion of the women of the colony did not ask for or desire the franchise. It is also asserted, we hope incorrectly, that a large proportion of the women will not use the franchise now that it has been bestowed upon them. The time has now gone by when the question of what women generally desired in this matter was of any real importance. It is not now a question of desire or no desire, of like or mislike. Parliament may have been mistaken, although we do not think it was, in its interpretation of women's wishes, but it is too late to consider that point. For good or for evil, whether it be regarded as a boon or a burthen, the franchise has been conferred upon the women of the colony, and it has become their duty to make the best possible use of the power with which they have been invested. It is no longer a matter of inclination — it has become one of duty. There is no going back in a matter of this kind. The step taken, wisely or unwisely, hastily or warily, cannot be retraced. If a mistake has been made, all that it remains possible to do is to endeavour to minimise the evil results— if the step is in the right direction then must the fullest possible advantage be taken of it.

To take an active, independent, and intelligent interest in the functions which constitutionally devolve upon them as electors has now become an almost sacred duty on the part of the women of the colony, and we cannot believe that they will prove unresponsive to the call, or careless in their performance. Much of the future of New Zealand depends upon them. A great power has been placed in their hands. They can neglect to use it; they can use it for ill; or they can make it operative for the greatest good to the country and to the community amongst whom they dwell. The sphere of their influence has been mightily enlarged. Instead of exercising only indirect power through their husbands, sons, or brothers, they are now charged with direct authority, and personal responsibility for its use or abuse. We trust they will remember this, and endeavour to realise the vast extent and importance of the new duties and new responsibilities which have in many cases, no doubt, been thrust upon them unwillingly and unsought for.

It is not in woman's nature to resist the call of duty. To make the best use of the franchise is now an imperative duty. It has been entrusted to them to counteract and in some measure lessen the evils which experience has proved to arise from universal Manhood Suffrage — the investment with political power of men of low intellect or vicious minds, who have in many cases debased the very manhood by which they have claimed and been allowed to exercise equal voting power with the most intellectual and virtuous of their sex. Women have been admitted to the exercise of votes with the hope and desire of elevating, improving, and purifying the whole electoral body. Can they turn away from the opportunity of doing this, and shirk their plain duty? They have been given votes that they may aid in the choice of men worthy to be entrusted with the guidance of the affairs of a young nation, and may secure the election of Parliaments whose aim will be to promote the material, the intellectual, and the moral welfare of the community, to ameliorate the social evils which unfortunately exist, and to establish the foundations of the State upon sound and enduring principles. Is not such a task worthy of the best energies of the best women? And the franchise has been given to women that they may raise and improve the status and prospects of their own sex, securing for them those equal rights, powers, and privileges in other things than politics which even-handed justice would confer, but which man, in the arrogance of sexual authority over those whom he has regarded as his inferiors, has too long denied.

- Editorial, Evening Post, 20 September 1893.

Seddon's antipathy to women's suffrage was no isolated case. The result of the suffrage bill was historic and hugely beneficial to New Zealand's reputation as a progressive nation, but the reasons underpinning the actual political decision-making that resulted in its passage were far more self-interested and paternalistic, as historian David Hamer explains:

New Zealand was celebrated as the first country in the world to give women the vote (in 1893). Yet within New Zealand the direct consequences of this are not easy to trace or define. Women may have been granted the vote, but they could not yet be Members of Parliament, let alone Cabinet Ministers. Behind the scenes wives of leading politicians such as Ballance, Seddon, Stout, and Reeves were able to exercise considerable influence, and there were some very influential and effective women government officials such as Grace Neill, Assistant Inspector of Hospitals. But for the most part, issues that were of concern to women had to be filtered through a system in which every position of power was held by a man. What emerged bore a close resemblance to what men thought was good for women rather than what women themselves may have thought. There was no attempt by the political parties to mobilise or appeal to women as a distinct political force, and no women's parties emerged to exploit on women's behalf the fact that they had received the vote. One reason why male politicians had been so ready to make the concession of the vote was that they were confident that women would not behave politically in this way. Much of the debate on giving the vote to women focused on the likely consequences for the temperance cause, it being assumed that they would vote overwhelmingly for a cause so strongly identified with the protection of family life. But the predictions were not borne out in any massive increase in the vote for prohibition. The emphasis in policy directed towards women was on the strengthening of the family unit rather than on the vote serving as some sort of lever to promote female emancipation, and women's organisations were on the whole prepared to support this.

- David Hamer, 'Centralisation and nationalism', in K. Sinclair (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of New Zealand, 2001, p.149-150.Even the male politicians in favour of women's suffrage were motivated by other concerns than the purity of expanding the democratic franchise. Self-interest was often the primary factor at work, as can be seen in this letter from senior statesman Sir John Hall:

...About Female Suffrage we must agree to differ - Your experience in the towns under the influence of strikes, may be an argument against women's suffrage, but in the country districts, and even throughout the Colony generally, it will increase the influence of the settler and family-man, as against the loafing single men who had so great a voice at the last elections. But for them all the country seats would have come to our side. I cannot believe that those who have anything to lose, will fail to bring to the poll, the female voters belonging to them. And generally among woman-kind the drunkard and the profligate will not have much chance, which will be a great gain for us...See also:

- Sir John Hall, writing to G.G. Stead, 30 June 1891, quoted in McIntyre & Gardner, Speeches and Documents on New Zealand History, London, 1971, p.204.

History: Election night 1931, 26 November 2011

History: Gold has been all-in-all to us, 4 October 2011

History: Bad meat and bad blood, 20 April 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment