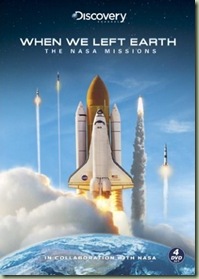

With this in mind, I rediscovered that sense of excitement at the thought of space travel when I settled down to watch a DVD copy of the Discovery Channel’s documentary mini-series, When We Left Earth. The six-part series examines the history of the NASA space programme from its earliest Mercury days, spurred on by JFK’s famous lunar ambition, through the Gemini and Apollo programmes, the Space Shuttle, Hubble, and the International Space Station of today.

The programme makers had superb interview subjects – basically every NASA astronaut of note including the famously reclusive Neil Armstrong appears to provide first-hand accounts of famous events as America learned how to fly in space and send men to the Moon in double-quick time. So we hear Apollo 16 mission commander John Young relate that it’s easy for him to remember what he was doing the moment he heard that the Space Shuttle programme had been approved by Congress: he was walking on the Moon. He celebrated the news with this famous leap:

(via NASA Images)

The documentary also features extraordinary film footage from NASA’s own comprehensive archives. Usually only glimpsed in snippets during TV news bulletins, the wealth of imagery brings home the stark beauty of the darkness of space and the pristine glory of a borderless Earth viewed from orbit. Extended sequences of lunar landing footage highlight the grand, bleak vistas of the Moon’s surface and the undisguised glee of the 12 men who were privileged to walk on its surface.

When We Left Earth is definitively NASA’s story rather than a broader review of space exploration. The publicity-garnering exploits of the Soviet space programme consistently pipped NASA at the post in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and these startling Soviet successes were a huge impetus to their American rivals, but the Soviets receive little coverage in the documentary. The USSR stole a march on the Americans with shoestring-budget projects and a flexible approach to risk management, and were able to tout a string of propaganda victories that would surely merit their own lavish documentary series:

- the launch of the first artificial satellite (Sputnik, 1957)

- the launch of the first animal in space (the dog Laika, 1957)

- the first man in space (Yuri Gagarin, 1961)

- the first woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova, 1963)

- the first spacewalk outside a space capsule (Alexei Leonov, 1965)

Sending humans into space atop burning rockets full of highly explosive fuel is an intrinsically dangerous endeavour, and the documentary examines the painstaking efforts of NASA ground support crews to ensure that the astronauts returned to Earth safely. The buzz-saw haircut of NASA’s stalwart mission controller Gene Kranz gets a lot of screen-time, with his no-nonsense pronouncements on the dramatic events of the Apollo 11 landing and the Apollo 13 near-disaster providing fascinating insights. But it is the footage of two momentous Space Shuttle missions that ultimately imbues these programmes with a powerful and poignant sense of history unfolding in front of the viewer.

As most people will know, the Space Shuttle programme suffered two catastrophic losses: the Challenger disaster in 1986 and the Columbia disaster in 2003. We have all seen the startling footage of the Challenger breaking up in its ascent phase, with its booster rockets flailing off on random ellipses as the main fuel tank explodes and the shuttle itself is consumed in the blast. The power of these images to shock is still every bit as potent as in 1986, but the documentary offers a broader picture. School teacher Christa McAuliffe was aboard Challenger and was to conduct a high-profile class lesson from orbit; the documentary interviews McAuliffe’s ‘alternate’, Barbara Morgan, the astronaut who would have taken McAuliffe’s place on Challenger’s crew if she had been unable to fly for medical or personal reasons. The sense of loss is enhanced by the mercifully brief snippets of film footage from Cape Canaveral on launch day, where we glimpse Morgan, distraught and clearly mortified at the loss of her friend and colleague. And to bring the calamity even closer to home, a mere second of contemporary TV footage is all that’s needed to show the dumbstruck grief of McAuliffe’s elderly parents, who were also in the crowd and witnessed the explosion.

The ineluctable sadness of the later Columbia disaster was not only that it was avoidable, but that the loss of the Challenger had not inspired a sufficient culture of vigilance in NASA. During its launch a hole had been punched in the Shuttle’s crucial under-wing heatshield, which led to the craft burning up on re-entry over the United States en route to its landing in Florida. All on board were lost. Columbia had spent a week in orbit working with the International Space Station, but NASA did not curtail its busy programme of space operations to check the underside of the Shuttle for damage before re-entry. If a check had been made the damage would surely have been noticed and the re-entry aborted.

The sheer quality of the NASA footage of the Columbia mission before the disastrous re-entry is a testament to the joy the astronauts experienced in their work, but also a sad indictment of the flaws of NASA’s safety policies. Certainly, NASA’s job is one of the hardest imaginable – balancing the insatiable desire of scientists to learn more about the universe and the questing goal of astronauts to experience the adventure of space flight, with the massive risks of venturing into the inhospitable environs of space using almost absurdly complex vehicles that have, in the words of the old astronaut joke, ‘been built by the lowest bidder’.

As NASA approaches uncertain times, with the Space Shuttle nearing obsolescence without any suitable replacement planned, When We Left Earth offers a valuable inside account of the US space programme, which at its peak was one of the defining aspects of late 20th century scientific endeavour. But the programme cannot tell us whether NASA will continue its work in space in its present form as the 21st century progresses, because that is by no means a certainty.

1 comment:

Sounds like a good documentary. Must seek it out.

(And I'm embarrassed to admit thhat I've never seen The Right Stuff - although I've been meaning to for years.)

Post a Comment