On Friday 17 September 1858, Captain W.H. Adams Jr piloted the great Royal Vauxhall Balloon for one last impressive show of night-time ballooning from the famed but now much-diminished Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. A splendid advertising poster from the time is displayed at the Museum of London alongside its excellent exhibit dedicated to the Gardens.

On Friday 17 September 1858, Captain W.H. Adams Jr piloted the great Royal Vauxhall Balloon for one last impressive show of night-time ballooning from the famed but now much-diminished Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. A splendid advertising poster from the time is displayed at the Museum of London alongside its excellent exhibit dedicated to the Gardens.

Adams had ballooned before at Vauxhall in 1856, but this was to be a special occasion, because the long tradition of pleasure gardens was coming to an end. London was remaking itself. This was the year of the Great Stink and the Joseph Bazalgette’s far-reaching modernisation of the city’s antiquated sewerage system, to the great benefit of public hygiene and the cleanliness of the Thames. The Gardens, too, did not form part of the new image of progressive London. After an abortive closure in 1841 due to the bankruptcy of its owners, the Gardens were finally closed for good in 1859 and the land sold for development to feed the need for building work in ever-expanding Victorian London, at the time the largest city in the world.

But what does this tell us about the Gardens and the place early aviation had in the public consciousness?

===

John Timbs’ 1855 book Curiosities of London recorded the early origins of the Gardens in ‘about 1661’ and visits thereafter by noted diarists like Evelyn and Pepys, and notes:

In England’s Gazetteer, 1751, the entertainments are described as ‘the sweet song of a number of nightingales, in concert with the best band of musick in England. Here are fine pavilions, shady groves, and most delightful walks illuminated by above 1000 lamps’ […]

[Author Oliver] Goldsmith thus describes the Vauxhall of about 1760: ‘The illuminations began before we arrived; and I must confess that upon entering the Gardens I found every sense overpaid with more than expected pleasure: the lights every where glimmering through scarcely moving trees; the full-bodied concert bursting on the stillness of night; the natural concert of the birds in the more retired part of the grove, viewing with that which was formed by art; the company gaily dressed, looking satisfied, and the tables spread with various delicacies – all conspired to fill my imagination with the visionary happiness of the Arabian lawgiver, and lifted me into an ecstasy of admiration. ‘Head of Confucius,’ cried I to my friend, ‘this is fine! This unites rural beauty with courtly magnificence’.

This lavish setting for night-time public recreation encouraged many thousands of fashionable Londoners – or at least, those who could afford the entrance fee – to journey to Vauxhall to see and be seen. It was popular with the young and not-so-young for courting purposes, because the many bowers and walks presented the perfect opportunity for genteel romance.

Canaletto painted a delightful daytime scene of the Gardens in around 1751, depicting small groups of immaculately-dressed worthies strolling along the grand walks at Vauxhall. The men boast ubiquitous curled white wigs, knee-length coats and fine britches tucked into knee-high white stockings, while women hobbled under the weight of enormously wide bustle dresses almost as wide as their height, which may have helped keep amorous gentlemen at a certain remove when walking side by side in public.

Timbs also notes that two of Fanny Burney’s novels boast Vauxhall scenes, including her famed Evelina, published in 1778 and quoted here in an extract in which the young heroine reveals how little of London she has actually seen:

‘Pray, Miss,’ said the son, ‘how do you like the Tower of London?’

‘I have never been to it, Sir’

‘Goodness,’ exclaimed he, ‘not seen the Tower! – why, may be, you ha’n’t been o’ top of the Monument, neither?’

‘No, indeed I have not’

‘Why, then, you might as well not have come to London for aught I see, for you’ve been no where’

‘Pray, Miss,’ said Polly, ‘have you been all over Paul’s Church yet?’

‘No, Ma’am’

‘Well, but, Ma’am,’ said Mr Smith, ‘how do you like Vauxhall and Marybone?’

‘I never saw either, Sir’

‘No – God bless me! – you really surprise me, – why Vauxhall is the first pleasure in life! – I know nothing like it. – Well, Ma’am, you must have been with strange people, indeed, not to have taken you to Vauxhall. Why you have seen nothing of London yet. However, we must try if we can’t make you amends’

Clearly in Burney’s tale it was unthinkable that anyone might not have partaken of the delights of Vauxhall, and indeed it was remiss of anyone to have not experienced them. (The Gardens also feature prominently and are often referred to in Thackeray’s 1847-8 masterpiece, Vanity Fair).

The second edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, published 1777-84, described the Vauxhall Gardens as ‘celebrated all over Europe for the entertainment they afford’ and set the scene as follows:

A noble gravel-walk, of about 900 feet in length, planted on each side with very lofty trees, which form a fine vista, leads from the great gate, and is terminated by a landscape of the country, a beautiful lawn of meadow-ground, and a grand Gothic obelisk […]

To the right of this walk, and a few steps within the garden, is a square, which, from the number of trees planted in it, is called the grove; in the middle of it is a magnificent orchestra of Gothic construction, ornamented with carvings and niches, the dome of which is surmounted with a plume of feathers, the crest of the prince of Wales. In fine weather, the musical entertainments are performed here. At the upper extremity of this orchestra a very fine organ is erected; and at the foot of it are the seats and desks for the musicians, placed in a semicircular form, leaving a vacancy at the front for the vocal performers. The concert is opened with instrumental music at six o’clock; which having continued about half an hour, the company are entertained with a song; and in this manner several other songs are performed, with sonatas and concertos between each, till the close of the entertainment, which is generally about 10 o’clock. A curious piece of machinery is exhibited about 9 o’clock, in a hollow on the left hand, about half-way up the walk already described, representing a beautiful landscape in perspective, with a miller’s house, a watermill, and a cascade. The grove is illuminated in the evening with about 1500 glass lamps; in the front of the orchestra they are contrived to form three triumphal arches, and are all lighted, as it were, in a moment.

However, in the 19th century the Gardens entered a steady decline. Charles Dickens, in Sketches By Boz in 1836, offers a wry critique of the Gardens in a relatively unfamiliar daytime visit, which in Dickens’ mind dispelled all the mystery and glamour of the place:

We walked about and met with disappointment at every turn; our favourite views were mere patches of paint; the fountain that had sparkled so showily by lamp light presented very much the appearance of a water pipe that had burst; all the ornaments were dingy and all the walks gloomy. There was a spectral attempt at rope dancing in the little open theatre; the sun shone upon the spangled dresses of the performers and their evolutions were about as inspiriting and appropriate as a country dance in a family vault.

In the same chapter Dickens describes the impressive launch of a balloon, during the period in which the Gardens were a prominent launching-place for balloon adventures:

Just at this moment all eyes were directed to the preparations which were being made for starting. The car was attached to the second balloon, the two were brought pretty close together, and a military band commenced playing, with a zeal and fervour which would render the most timid man in existence but too happy to accept any means of quitting that particular spot of earth on which they were stationed. Then Mr. Green, sen., and his noble companion entered one car, and Mr. Green, jun., and HIS companion the other; and then the balloons went up, and the aerial travellers stood up, and the crowd outside roared with delight, and the two gentlemen who had never ascended before, tried to wave their flags, as if they were not nervous, but held on very fast all the while; and the balloons were wafted gently away, our little friend solemnly protesting, long after they were reduced to mere specks in the air, that he could still distinguish the white hat of Mr. Green. The gardens disgorged their multitudes, boys ran up and down screaming 'bal-loon;' and in all the crowded thoroughfares people rushed out of their shops into the middle of the road, and having stared up in the air at two little black objects till they almost dislocated their necks, walked slowly in again, perfectly satisfied.

The next day there was a grand account of the ascent in the morning papers, and the public were informed how it was the finest day but four in Mr. Green's remembrance; how they retained sight of the earth till they lost it behind the clouds; and how the reflection of the balloon on the undulating masses of vapour was gorgeously picturesque; together with a little science about the refraction of the sun's rays, and some mysterious hints respecting atmospheric heat and eddying currents of air.

Despite this decline, or perhaps because of it, the organisers spared little expense in laying on grand spectacles for the attending worthies, in the hope that Vauxhall would maintain its reputation as the place for fine folk to indulge in public recreation. And it is noteworthy that one of the grandest shows available in the Victorian world – the fiery night-time ascent of a hot-air balloon – was booked in 1858, in the hope of concluding the Vauxhall story with a theatrical flourish.

Hence the appearance of the fine advertising poster above, calling the public’s attention to the ‘Last Grand Night Ascent!’ of the venerable and famous Royal Vauxhall Balloon. In November 1836 the balloon had flown three aeronauts (including Mr Charles Green, mentioned by Dickens above) from Vauxhall across the English Channel to Weilburg in Nassau, Germany. The international journey of 608km in 18 hours caused a great sensation and made a celebrity of Green and his balloon, which was for a time renamed the Great Nassau Balloon. It also set a distance record for ballooning that was not bested until 1907. (The Charles Green Salver is still awarded to mark notable feats of ballooning today). In the 1870 book Wonderful Balloon Ascents, by the splendidly pseudonymous Fulgence Marion (aka Monsieur Camille Flammarion), one of Green’s passengers recounts the spectacle of crossing the Channel:

"It was forty-eight minutes past four," says Monk-Mason, "that we first saw the line of waves breaking on the shores beneath us. It would have been impossible to have remained unmoved by the grandeur of the spectacle that spread out before us. Behind us were the coasts of England, with their white cliffs half lost in the coming darkness. Beneath us on both sides the ocean spread out far end wide to where the darkness closed in the scene. Opposite us a barrier of thick clouds like a wall, surmounted all along its line with projections like so many towers, bastions, and battlements, rose up from the sea as if to stop our advance. A few minutes afterwards we were in the midst of this cloudy barrier, surrounded with darkness, which the vapours of the night increased. We heard no sound. The noise of the waves breaking on the shores of England had ceased, and our position had for some time cut us off from all the sounds of earth."

===

While hot air ballooning remained a spectacle of public interest in the 1850s, the limitations of ballooning as a form of transport meant that it never become commonplace. While balloons did prove useful for military observation purposes, it was not possible to reliably direct the flight of balloons until the early 1900s, and even then lighter-than-air flight by ballooning was soon eclipsed by the growing confidence of heavier-than-air fliers following the Wright Brothers’ historic success in 1903. In a way, then, it is somehow fitting that the faded glory of the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens was celebrated by a mode of transportation that was in its own way already approaching obsolescence.

Historian David Coke records the scene at the Gardens’ final night in 1859, and what came afterwards:

Vauxhall Gardens finally closed after the 'Last Night for Ever' on 25 June [July?] 1859. Many reasons are given for this. The proprietors at the time blamed the magistrates who continually banned their most popular attractions as either too dangerous, or too disruptive to the newly-respectable neighbourhood of Kennington. But other factors certainly played a part: Vauxhall Gardens itself had become run down and tawdry, and was considered old-fashioned; the railway, which ran past the main entrance, had made travel further afield much easier and cheaper; seaside towns, with their Vauxhall-like piers were becoming fashionable; and, finally, the site itself was too valuable as property, and the blandishments of developers eventually persuaded the proprietors to cut their losses and sell the lease.

Amongst the first buildings on the site was St Peter's Church, Kennington Lane, which is located roughly on the site of the Neptune Fountain at the end of the Grand South Walk. The rest of the area was divided up into three hundred building plots, and Vauxhall Gardens disappeared, apparently for ever. In the Blitz, however, the site was cleared, and is now a park, with a city farm at one end, allowing us to see the extent of the original gardens. Vauxhall Gardens, and the surrounding streets, are now, 150 years too late, a conservation area.

Now the site of the Gardens is blocked off from the Thames not only by busy railway lines and Vauxhall Station, but also the Albert Embankment and the modernist edifice of the MI6 headquarters. But for several decades in the 19th century, up to Captain Adams’ flight in September 1858, the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens could stake a claim of being London’s original airport, and a very stylish one at that.

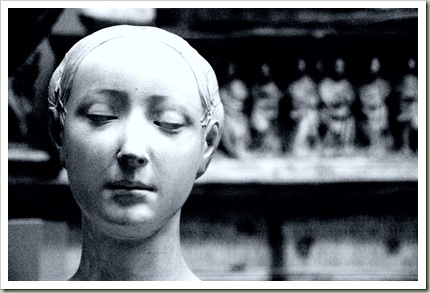

1860s cast of a marble bust of an unknown woman, perhaps Sigligaita Rufolo, from the Cathedral at Ravello on the Amalfi coast in southern Italy, c. 13th century.

1860s cast of a marble bust of an unknown woman, perhaps Sigligaita Rufolo, from the Cathedral at Ravello on the Amalfi coast in southern Italy, c. 13th century.

A marvellously haughty personage carved by sculptor Andrea dell’Aquila in the second half of the 15th century. The original is in the Bode Museum in Berlin, where this cast was taken in 1889-91.

A marvellously haughty personage carved by sculptor Andrea dell’Aquila in the second half of the 15th century. The original is in the Bode Museum in Berlin, where this cast was taken in 1889-91.