Modestly adventurous, while also endeavouring to look both ways when crossing the road.

26 October 2009

Eastern Beach

Check ignition and may God’s love be with you

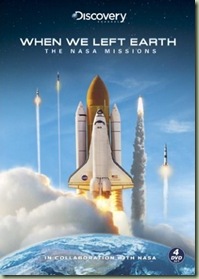

With this in mind, I rediscovered that sense of excitement at the thought of space travel when I settled down to watch a DVD copy of the Discovery Channel’s documentary mini-series, When We Left Earth. The six-part series examines the history of the NASA space programme from its earliest Mercury days, spurred on by JFK’s famous lunar ambition, through the Gemini and Apollo programmes, the Space Shuttle, Hubble, and the International Space Station of today.

The programme makers had superb interview subjects – basically every NASA astronaut of note including the famously reclusive Neil Armstrong appears to provide first-hand accounts of famous events as America learned how to fly in space and send men to the Moon in double-quick time. So we hear Apollo 16 mission commander John Young relate that it’s easy for him to remember what he was doing the moment he heard that the Space Shuttle programme had been approved by Congress: he was walking on the Moon. He celebrated the news with this famous leap:

(via NASA Images)

The documentary also features extraordinary film footage from NASA’s own comprehensive archives. Usually only glimpsed in snippets during TV news bulletins, the wealth of imagery brings home the stark beauty of the darkness of space and the pristine glory of a borderless Earth viewed from orbit. Extended sequences of lunar landing footage highlight the grand, bleak vistas of the Moon’s surface and the undisguised glee of the 12 men who were privileged to walk on its surface.

When We Left Earth is definitively NASA’s story rather than a broader review of space exploration. The publicity-garnering exploits of the Soviet space programme consistently pipped NASA at the post in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and these startling Soviet successes were a huge impetus to their American rivals, but the Soviets receive little coverage in the documentary. The USSR stole a march on the Americans with shoestring-budget projects and a flexible approach to risk management, and were able to tout a string of propaganda victories that would surely merit their own lavish documentary series:

- the launch of the first artificial satellite (Sputnik, 1957)

- the launch of the first animal in space (the dog Laika, 1957)

- the first man in space (Yuri Gagarin, 1961)

- the first woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova, 1963)

- the first spacewalk outside a space capsule (Alexei Leonov, 1965)

Sending humans into space atop burning rockets full of highly explosive fuel is an intrinsically dangerous endeavour, and the documentary examines the painstaking efforts of NASA ground support crews to ensure that the astronauts returned to Earth safely. The buzz-saw haircut of NASA’s stalwart mission controller Gene Kranz gets a lot of screen-time, with his no-nonsense pronouncements on the dramatic events of the Apollo 11 landing and the Apollo 13 near-disaster providing fascinating insights. But it is the footage of two momentous Space Shuttle missions that ultimately imbues these programmes with a powerful and poignant sense of history unfolding in front of the viewer.

As most people will know, the Space Shuttle programme suffered two catastrophic losses: the Challenger disaster in 1986 and the Columbia disaster in 2003. We have all seen the startling footage of the Challenger breaking up in its ascent phase, with its booster rockets flailing off on random ellipses as the main fuel tank explodes and the shuttle itself is consumed in the blast. The power of these images to shock is still every bit as potent as in 1986, but the documentary offers a broader picture. School teacher Christa McAuliffe was aboard Challenger and was to conduct a high-profile class lesson from orbit; the documentary interviews McAuliffe’s ‘alternate’, Barbara Morgan, the astronaut who would have taken McAuliffe’s place on Challenger’s crew if she had been unable to fly for medical or personal reasons. The sense of loss is enhanced by the mercifully brief snippets of film footage from Cape Canaveral on launch day, where we glimpse Morgan, distraught and clearly mortified at the loss of her friend and colleague. And to bring the calamity even closer to home, a mere second of contemporary TV footage is all that’s needed to show the dumbstruck grief of McAuliffe’s elderly parents, who were also in the crowd and witnessed the explosion.

The ineluctable sadness of the later Columbia disaster was not only that it was avoidable, but that the loss of the Challenger had not inspired a sufficient culture of vigilance in NASA. During its launch a hole had been punched in the Shuttle’s crucial under-wing heatshield, which led to the craft burning up on re-entry over the United States en route to its landing in Florida. All on board were lost. Columbia had spent a week in orbit working with the International Space Station, but NASA did not curtail its busy programme of space operations to check the underside of the Shuttle for damage before re-entry. If a check had been made the damage would surely have been noticed and the re-entry aborted.

The sheer quality of the NASA footage of the Columbia mission before the disastrous re-entry is a testament to the joy the astronauts experienced in their work, but also a sad indictment of the flaws of NASA’s safety policies. Certainly, NASA’s job is one of the hardest imaginable – balancing the insatiable desire of scientists to learn more about the universe and the questing goal of astronauts to experience the adventure of space flight, with the massive risks of venturing into the inhospitable environs of space using almost absurdly complex vehicles that have, in the words of the old astronaut joke, ‘been built by the lowest bidder’.

As NASA approaches uncertain times, with the Space Shuttle nearing obsolescence without any suitable replacement planned, When We Left Earth offers a valuable inside account of the US space programme, which at its peak was one of the defining aspects of late 20th century scientific endeavour. But the programme cannot tell us whether NASA will continue its work in space in its present form as the 21st century progresses, because that is by no means a certainty.

23 October 2009

The Wintergarden

The Auckland Domain’s Wintergarden hothouses, located a few hundred metres from the War Memorial Museum, have been a fixture of the city’s botanical attractions for nearly 90 years. Opened on 12 October 1921 ‘for the benefit and pleasure of the public’, the project was paid for using the surplus funds of the remarkably successful Auckland Exhibition of 1913-14. A pair of glass hothouses is linked by an outdoor promenade featuring a stylish rectangular lily pond fed by bubbling fountains and fringed by classically-styled statues. Previously the Wintergarden had languished in a state of disrepair, but since a recent refurbishment it’s regained its rightful place as a much-valued small oasis of calm in the middle of Auckland.

10 October 2009

Take the ‘A’ train

In contrast to Wellington’s trains, which I use whenever possible, in the past I’ve seldom used Auckland’s rather meagre train network. The last time I can remember was probably 10 years ago, when I had been dropped off for a meeting in Henderson and decided to take the train back to Newmarket rather than take a long bus ride. As I’m from Onehunga and still stay there when I’m in Auckland, the train stations along the main trunk line are just too far away for me to use with ease. Things will be different when the branch line to Onehunga finally reopens in 2011 – I look forward to trying it out – but for the time being taking the train to town isn’t practical.

Still, when there’s no buses you have to make an effort. Fortunately I was able to get a lift down to the nearest train station, Penrose. While not particularly rundown, Penrose station isn’t exactly a welcoming place. Once you’ve descended from the over-track walkways down to the platform you have to bypass the old wooden station building, which is all boarded up now, and walk another 50 metres or so to get to the raised platform that’s currently in use. There’s a small shelter but it’s pretty exposed to the elements, and the platform isn’t the sort of place you’d want to hang around after dark – it’s in the middle of an industrial zone with almost no people around. There’s no ticket booth; you buy your ticket on the train. On the plus side there’s a well-designed timetable and network map explaining how to use the service, and it hadn’t been graffitied yet.

A couple of southbound trains rattled past, a reminder that Auckland’s still beset with its outdated diesel trains designed to pull freight rather than passenger carriages. One five-carriage train pulled up with a massive diesel unit at each end, and both engines were roaring as it departed. No fun living near the train tracks with those monsters going past four times an hour.

My northbound train to Britomart downtown arrived seven minutes late, which was noticeable but no major inconvenience. It was at about three quarters capacity, which is impressive given it was midday on a weekday. A ticket to Britomart (see picture above) only cost $3.80, which is 50c cheaper than the bus, and whereas a bus ride to town would take around 50 minutes from Onehunga, this trip only took 20 minutes.

The return trip from Britomart was equally efficient, leaving on time and costing only $2.80 because I decided to try getting off one stop early at Ellerslie and walking home from there. Certainly, it’s a fairly deserted neighbourhood and you have to cross the heaving Great South Road traffic, and ultimately the walk home was impractical at 35 minutes. But it was an interesting experiment, and I can see why public transport advocates feel frustrated at the limitations of planning and policy around Auckland’s train network. If only the public transport network was better integrated with feeder buses running to train stations and secure park and ride services for commuters, then it would be much easier to convince more Aucklanders to reduce their reliance on congestion and pollution-creating private car journeys to travel about the city.

(Disclaimer: To anyone from outside New Zealand, a blog post about ‘how I caught a train’ might seem a laughably trivial subject to cover. But in Auckland the importance of passenger rail links has long been subjugated to the roading imperatives of local and central government, and as a result Auckland has been dominated by cars and motorways for the past 50 years. Sadly, ‘how I caught a train’ stories are all-too-uncommon in Auckland.

A slice of the country

07 October 2009

The beautiful things

These days New Zealand is pretty much like any other well-off Western nation. Perhaps not as wealthy as many of its OECD colleagues, and with its economy dented by the global recession, certainly, but on the whole the standard of living is comfortable. Like most such societies, consumerism is a dominant lifestyle, and homes are decked out with a wide range of appliances in virtually every room. The 1980s saw most households acquire a VCR; in the ’90s many New Zealanders bought personal computers; in the late 2000s, the appliance that seems to be attaining ubiquity is the heat pump, designed to ward off the soggy winter chills in our poorly-insulated houses.

But it’s not so long ago that New Zealand households were substantially less cluttered with appliances, and the items we now consider to be mandatory were pigeon-holed as luxury items for the privileged few. New Zealand’s isolation was part of the problem in the first half of the 20th century – we were just too far from the manufacturers of modern appliances for them to reach our shores and stores in any number. New Zealand’s own light manufacturing industries struggled to keep pace with consumer demands for new appliances.

New-fangled gizmos like electric ovens seemed so peculiar to a nation brought up using wood, coal or gas-fired cooking stoves that a cautionary guide was issued by bookseller Whitcombe & Tombs to educate the cooking public (i.e. housewives):

Using an electric oven

- Before using a new oven turn top and bottom elements to ‘Full’ heat and leave them until the oven has attained a temperature of 400 degrees. Then turn both elements off. This will destroy any loose ends of packing, grease, or anything which has accumulated in the oven during the process of manufacture, and which might cause odours.

- An electric oven must never on any account be heated to a greater temperature than 600 degrees [315 Celsius]. There is nothing that needs a temperature as great as this in baking.

- An oven which is allowed to overheat will usually destroy the thermometer, and probably damage the oven fabric.

- When the oven has reached the correct baking temperature it is rarely necessary to use the top element. In almost every case actual baking is done without top heat.

Do not open the oven door when baking. A combination of the recipe time and your own good judgement will render it quite unnecessary.

- Whitcombe’s Modern Home Cookery and Electrical Guide, Christchurch, c.1940, quoted in Richard Wolfe, Instructions for New Zealanders, 2006

The introduction of refrigerators was also a relatively recent step, occurring predominantly after World War 2, but many houses (including my grandparents’) made do without one well into the 1950s. Shoppers purchased perishable goods daily from nearby corner shops and stored them in cold safes - air-cooled cupboards that can still be found in older homes. The one my grandparents’ house in Onehunga is a simple cupboard at floor level with a wire mesh base that allows air to circulate from under the house, thereby cooling the contents of the safe.

I’ve recently been reading an excellent collection of Frank Sargeson short stories, and in one in particular story set in 1940 the lure of modern appliances is prominent as a man fends off his wife’s demands for a refrigerator:

Not to mention a car, one thing she’s always on about is a refrigerator. It would save money in the long run is what she reckons, and maybe she’s right, but it’s always seemed too much of a hurdle to Jack.

Do you know dear, I heard him say once, when I was a little boy, and my mother opened the safe, and there was a blowfly buzzing about, it sometimes wouldn’t even bother to fly inside.

And Mrs Parker said, What’s a blowfly (or your mother for that matter) got to do with us having a refrigerator? And Jack went on grinning until she got cross and said, Well why wouldn’t it fly inside?

Because dear, Jack said, it knew it was no good flying inside.

And you could tell it annoyed his missis because she still couldn’t work it out, but she wasn’t going to let on by asking Jack to explain.

- Frank Sargeson, ‘The Hole that Jack Dug’, published 1945

As mentioned in the first paragraph of the excerpt above, a family car was often the ambition of families who lacked one, and today’s car-dependent multi-vehicle households would probably shudder at the idea of living without private vehicles. Yet until the 1950s, when tramlines in Auckland were killed off and suburban sprawl really kicked in, car ownership was far from ubiquitous.

Until the mid-1950s Aucklanders and residents of the other major towns in New Zealand relied on walking (a.k.a. Shanks’ pony), cycling, buses, or the excellent tram network that served much of the Auckland isthmus. This intricate diagram, linked to by Joshua Arbury’s Auckland transport blog, shows the extent of the tram services offered until the network was shut down on 29 December 1956. If only we still had them!

In the 1960s there was a rapid expansion of car ownership in New Zealand, setting the scene for the transformation of New Zealand cities to a focus on private car transportation rather than public transport. In the five years from 1967 to 1971 the number of cars in New Zealand rose from 781,047 to 908,253 - an increase of 16 percent at a time when the national population only increased by five percent. The rapid rise in car ownership can be seen in these figures:

Total population per licensed car, 1961-71

| As at 31 March | Persons per car | As at 31 March | Persons per car |

| 1961 | 4.6 | 1967 | 3.5 |

| 1962 | 4.5 | 1968 | 3.4 |

| 1963 | 4.3 | 1969 | 3.3 |

| 1964 | 4.1 | 1970 | 3.3 |

| 1965 | 3.8 | 1971 | 3.1 |

| 1966 | 3.7 |

Source: New Zealand Official Yearbook 1972, Department of Statistics, Wellington, 1972, p.311

04 October 2009

Down and out in America

Paul (John Diehl), a Vietnam vet gripped with the possibilities of further terrorist attacks on the US, has set up his battered old van as a mobile surveillance centre, and trawls the streets of Los Angeles looking for the next atrocity. Paul hasn’t seen Lana (Michelle Williams), his niece, since she was a baby, but now she flies back to LA after a lifetime spent with her missionary parents in Africa and working on the West Bank. She returns to find her uncle and pass on an important message from her mother, and finds refuge with a friend who runs a downtown mission shelter where LA’s homeless find food and shelter. Paul is initially reluctant to meet Lana, seeing it as an unwelcome distraction from his important anti-terrorist mission, but when they both witness a shocking drive-by murder of Hassan, one of the shelter’s homeless people, they are driven together: Paul because he suspects Hassan was involved with a terrorist plot, and Lana because she had spoken to Hassan before he was murdered and wants to find his relatives out of compassion.

It is these two intertwined themes that drive the film. Paul’s hyper-tense security paranoia in which boxes of chemicals are invariably destined for terrorist bomb-making plots, leads him to suspect the turban-wearing foreigner Hassan of a criminal conspiracy. Lana’s diametrically opposed socially-conscious worldview, leads her to empathise with the murdered Hassan and see the human story behind the stereotypes. Together, Paul and Lana journey to return Hassan’s body to his brother in a desolate provincial town; Lana as an act of human charity, and Paul because he’s certain there’s a dark plot at the heart of it all.

These are solid ideas on which to base a film, and Land of Plenty manages to portray the homelessness situation in downtown Los Angeles with commendable accuracy. The New York Times’ A.O. Scott argued that the film ‘is like a clumsy, well-meaning intervention in a family quarrel. Mr. Wenders may not have the power to heal the rifts his movie acknowledges - and his account of them may not always be persuasive - but there is nonetheless something touching about his heartfelt concern’.

But ultimately the speed with with the film was created detracted from its ability to handle the complex issue of Paul’s post-9/11 paranoia. The script feels underworked and doesn’t offer the viewers any particularly profound insights into the characters’ individual philosophies. It’s as if the writers (Wenders and colleague Michael Meredith) knew where they wanted the story to go and filled in the gaps around that objective, but lacked the time to fine-tune the script into something more significant. The man who created the hugely influential Paris, Texas and the beautiful Wings of Desire could have achieved better results with more time. As it stands there’s nothing memorable about the dialogue, which from a director of Wenders’ calibre is unusual. There are also several small but noticeable plot holes.

Diehl and Williams do their best with the material, and their performances are commendable considering the relatively sparse resources they have to draw on. Land of Plenty was made for under a million dollars, shot in 16 days, and the whole film was written and produced in about three months.

Perhaps the circumstances in which the film was made dictated the approach Wenders took. Fitting the project into a few spare months meant that quick-fire methods had to be adopted. In keeping with the social justice themes being portrayed in the homeless shelter scenes, Wenders also approached his cast and crew remuneration in an egalitarian manner. According to IMDB, cast and crew were all paid the same US$100 daily rate, including the lead actors.

Land of Plenty wears its European sensibilities on its sleeve. Making a film about anti-terrorist paranoia in America in 2004, when the invasion and occupation of Iraq was still in its early stages, would have been controversial if any American backing had been required. Its critique of the American psyche may be somewhat scattershot, but given the climate of the time, it was a brave move – particularly from its American lead actors.

The talented Michelle Williams has shown her commitment to such small projects in her career, recently having appeared in the excellent Wendy and Lucy (2008), one of the films I particularly admired at the recent New Zealand Film Festival. A sensitive performance from Williams in that film depicted the travails of poverty in recession-hit America. The quality of Wendy and Lucy shows that independent films with strong messages of social justice can be made on small budgets. Perhaps Land of Plenty could have benefitted from another month or two of production time to produce a work of more lasting authority, rather than a project with considerable promise that was only partially fulfilled.